According to plans announced some time ago the USGS is going to stop recording images with Landsat 7 at the end of September, ending routine operation of the satellite after more than 20 years.

Like EO-1 where i discussed this matter in more depth, Landsat 7 has run out of fuel to maintain its orbit and has started drifting to earlier morning recording times. This drift has not progressed as much as with EO-1 in 2017 yet but it is visible in the images recorded in the form of longer shadows quite well.

In addition the USGS has lowered the orbit of the satellite some time ago to make space for Landsat 9.

Landsat 7 is in particular noteworthy historically because it is Landsat 7 imagery that has shaped the public perception of Landsat as a source of earth observation images more than any of the other Landsat satellites. That is mostly because Landsat 7 was the newest Landsat satellite and the main source of Landsat imagery when the Landsat program moved to an open data distribution policy and during much of the period of popularization of Landsat data that followed (see the history of the Landsat satellites).

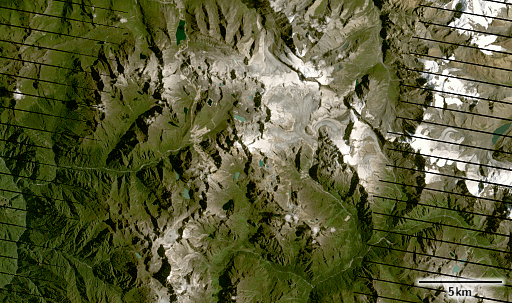

The strange thing about this is that Landsat 7 was struck by a major failure in its imaging system (known as the SLC failure – standing for scan line corrector) only four years after beginning of observations in 1999. The failure massively reduced the usability of Landsat 7 data for many, in particular for visualization application. So while the public image of Landsat has largely been formed by Landsat 7 recordings, it has predominantly been images from 1999-2003 that have contributed to that. These about 20 year old images are still widely used in popular map services these days, most notably Bing Maps, but also nearly universally by almost all map services for the Antarctic (though you can now get a more up-to-date alternative meanwhile of course ;-))

Technologically and in terms of image quality Landsat 7 is a bit of a relic from another time. Even compared to other satellites launched around the same time (like Terra in 1999 and EO-1 in 2000) Landsat 7 was using conservative technology for its imaging system, with only smaller improvements compared to what had already been used for Landsat 6 in 1993, which failed on launch.

The most significant constraint of Landsat 7 data in terms of image quality is the rather limited dynamic range of the sensor and as a result the high noise levels in dark areas and frequent overexposure in bright areas. The design tried to mitigate that limitation by offering two different amplification settings of the sensor which were chosen based on the expected brightness of the earth surface in the area. As a result of this limitation the USGS stopped recording areas with particularly high contrast (that is especially polar regions) and concentrated the recording capacity of Landsat 7 on the main lower latitude land masses.

Another noteworthy aspect of Landsat 7 was that its high resolution panchromatic spectral band extended across both the visible range and the near infrared, which made its use for producing high resolution natural color images difficult and subject to artefacts in case contrast in the near infrared is significantly different from that in visible light. It shares this characteristic with many higher resolution commercial satellite sensors – both back then but even today. You can see that in the images shown here comparing the appearance in Landsat 7 and Landsat 8 images.

Despite these limitations – for the needs of most data users it seems to have been fairly sufficient for most of the operational history of the satellite. The rather slow adoption of Landsat 8 by data users after 2013 pretty strongly supports this impression. In a way that is also the business model of Landsat overall so far – continuity before innovation.

The future of Landsat

Landsat 7 is being replaced directly by Landsat 9 in its orbit and therefore recording schedule. I have yet to write about Landsat 9 in more depth which i have not yet gotten around to. That means we now have a two Landsat satellite constellation with a combined revisit time of 8 days and with both satellites having almost the same capabilities.

What comes after Landsat 9 is still unclear. The most recent publicly available update i could find is here – but this is not providing much more in substance than this and is still rather vague and at the same time it is unclear to what extent what is presented there as what will be (which in a nutshell looks very much like a Sentinel-2 clone with additional spectral bands) is actually already decided on the actual decision making level. In particular everyone should keep in mind that during the early considerations for Landsat 10/Landsat Next the idea was discussed to depart from the full open data model. And there is no clear statement so far that this is not under consideration any more. The existence of Sentinel-2 makes this somewhat unlikely (because with a free alternative there would not be much of a business case for non-free data in a very similar quality and timeliness range). The 10m resolution number that has been widely communicated as target around future Landsat systems is interesting in that regard because this is what now – thanks to Sentinel-2 – is the division line between what is available as open data and what is only commercially available. If Landsat does not go beyond that the status quo would be kind of preserved. If Landsat would move to higher spatial resolution, however, that would massively cut into the domain of commercial satellite operators. In other words: It would probably be politically unfeasible for Landsat planners to try going beyond 10m spatial resolution.

On the other hand a future Landsat with a 10m base resolution would mean an increasing gap between low and high resolution systems with nothing in sight so far to bridge that gap. Let me explain: Over the past decades (essentially since 1999) the main global open data visible light image sources we had were:

- MODIS (since 1999/2002, near daily coverage at two times of day) at 250m resolution

- Landsat (since 1999, every 16 days – 8 days with Landsat 5/7 and after Landsat 9 became operational) at 15m reolution (30m multispectral)

With both MODIS satellites reaching their end of life now and no direct replacement being planned we will in the future have from the US:

- VIIRS (since 2011/2017 + another planned for 2022, daily coverage at 2(3) times of day) at 375m resolution

- Landsat Next (probably 2030+, probably less than one week revisit interval) at 10m resolution

From the EU we have in addition:

- Sentinel-3 OLCI with near daily coverage at 300m resolution

- Sentinel-2 with 5 day revisit (but no complete recording of all land masses in practical operation) at 10m resolution

There is not much in between though, just the Japanese GCOM-C at 250m resolution and Amazonia-1 from Brazil at 60m resolution (which is not operated for world wide recording apparently). But neither of them offers a substantially better revisit frequency than the two satellite Sentinel-2 constellation. This means as a data user you practically have to either work with a resolution of 375m or 300m or go to a much higher resolution but deal with the disadvantage of a a low recording frequency and a large data volume to process.