Generalizing rivers and lakes - Introduction

In December last year i wrote about the generalization of coastlines. Of course coastlines are not the only elements in most maps and including the inland waterbodies, i.e. rivers and lakes, is the logical next step.

Why generalization

I explained some of the background of why generalization is important for well readable maps in the text about the coastlines but in fact it is even more important for rivers and lakes. The coastlines have been a nice test case since the effect on the readability of maps can be easily seen and because of the way the coastline is processed by Openstreetmap which ensures a consistent data set being available as a basis. This is different for the other waterbodies for which the data is much less uniform - i am discussing this in more detail in a separate article.

The inland waterbodies form a complex interconnected system as part of the ![]() global water cycle. And although the coastline tends to be the most recognizable element of physical geography in a map there is much more that can be read from the rivers and lakes when viewing a map than from the coastline. But to do so we must be able to see this structure in the waterbodies when looking at the map and we can only do that when the rendering is well readable.

global water cycle. And although the coastline tends to be the most recognizable element of physical geography in a map there is much more that can be read from the rivers and lakes when viewing a map than from the coastline. But to do so we must be able to see this structure in the waterbodies when looking at the map and we can only do that when the rendering is well readable.

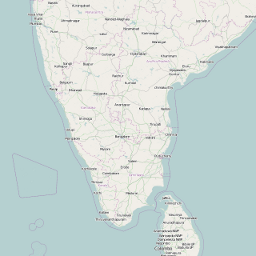

The following examples from Openstreetmap and Google Map both show rivers and lakes in southern India but in neither of them you can actually see anything beyond there is some water here at various places in the map (you can click on the map for a full size display). To actually gain something from looking at the waterbodies in terms of understanding the geography of the area would require a better readability. The third example shows my current demo map from this area where you can see the rivers and lakes much more clearly including for example the fact that all larger rivers flow to the eastern coast while originating mostly from the mountains in the west (the ![]() Western Ghats).

Western Ghats).

|

|

|

| OpenStreetMap | Google Map | imagico.de |

Granted the lack of any labels, roads and borders like in the other maps also helps visibility of the water features but the primary reason why they can be better seen (including several smaller errors) is the generalization.

How to generalize river and lakes

Most classical print maps display waterbodies in two or three different forms:

- large water areas (like lakes or wide rivers) are displayed as filled areas, usually with an outline in addition. The style might be different for rivers and lakes although this is not very common.

- less important rivers are shown as uniform color lines, often with the same or a similar color as the outlines of the lakes

- in some maps (but not in all) important rivers are shown as a constant width line with additional outline. Others vary the river line width as an indicator for the river size.

Here a few practical examples on how this looks like (click on images to show in larger):

|

|

|

| Congo river in Operational Navigation Chart | Río de la Plata in Diercke Weltatlas | Yukon river in Kümmerly+Frey Internationaler Atlas |

As can be easily seen the tagging commonly used for waterbodies in Openstreetmap quite closely represents this map rendering scheme. The problem is however that the selection of features, i.e. what is large/important and small/less important in the list above depends on the map scale. To somewhat support rendering maps at varying scales as well as for other purposes like routing it is encouraged to always map a river line in the center of a river (waterway=river) even if there is a riverbank polygon. This is however not consistently done - there are many rivers in OSM data without a centerline.

The problem of generalizing the waterbodies to be displayed in such form while being well readable can be considered to consist of two separate questions – First: which of the waterbody features should be selected for display and second: how should they be rendered.

For a map rendering scheme as described above there are two feature selection steps:

- Select the water areas that are large enough to be shown as water areas at the map scale in question. Using the polygon's area for this is not a good idea, the primary criterion will have to be the minimum width of the water areas since the outlines are not supposed to touch. This is best handled differently from the coastlines though: While a peninsula should never be turned into an island it is sometimes acceptable and useful to split a waterbody into several parts. An iconic example for this is

Lake Michigan–Huron where the two basins are connected by a narrow passage but which are often shown as separate lakes.

Lake Michigan–Huron where the two basins are connected by a narrow passage but which are often shown as separate lakes. - Select the important and less important rivers to be rendered in the two different forms – or only one class of rivers. The big question here is what measure to use for the importance of a river. The most obvious quantities would be the river width or the average discharge. Both of these turn out to be problematic for this purpose at a closer look though. While rivers often get wider and increase in discharge along their course the width can significantly decrease in narrow valleys and gorges and in dry regions the discharge can reduce due to evaporation (the

Niger river being a prominent example). As a result rivers could be interrupted in display if the smaller middle part does not meet the cutoff while the upper and lower parts do. This should not happen though. To create an importance measure that reliably satisfy this condition requires knowledge of the flow patterns of the whole river network.

Niger river being a prominent example). As a result rivers could be interrupted in display if the smaller middle part does not meet the cutoff while the upper and lower parts do. This should not happen though. To create an importance measure that reliably satisfy this condition requires knowledge of the flow patterns of the whole river network.

In most print maps like in the examples above this selection is done manually, either specifically for the map in question or the importance ratings required for the selection process have been determined in advance and are part of the data used. For a web map with multiple map scales and a constantly evolving data source this is difficult of course so an automated process could be very useful.

In principle the selection could be done independently for the line and area features. Since the width the river lines are drawn in will usually be larger than the actual river width while the area features are shown in their real size (possible modified by the later steps in the generalization process) there are some interdependencies between those two though. Also in case of the Openstreetmap the line and area features are normally rendered together in the same color so it is not safe to assume either of these can be used without the other.

The key problem

The key problem of the whole feature selection step which is also going to be one of the primary difficulties of the whole generalization process is that properly assessing the importance of the rivers for performing the selection requires processing every river network or watershed as a whole. Since the boundaries of the watersheds are not precisely known and some of the river networks span whole continents this essentially requires processing the whole planet at once - or at least whole continents.

So much for feature selection in theory. In the second part i will explain the practical problems of doing this using the Openstreetmap waterbody data for the whole planet.

Visitor comments:

no comments yet.

By submitting your comment you agree to the privacy policy and agree to the information you provide (except for the email address) to be published on this website.